The existence of “zombie” firms is a dangerous and growing problem in the global economy. These are companies that would normally have gone bankrupt or been restructured but have been kept alive by sympathetic credit policy and interest rates which are artificially and extraordinarily low.

Economists and strategists are also becoming very worried about the impact the growth of these firms is having. We are joining these voices, and this article outlines three conclusions we have drawn on the issue:

- It represents an inefficient allocation of capital.

- It will depress future economic growth.

- It may help to explain the underperformance of Value1 over the last 10-12 years.

Creative Destruction and Monetary Policy

An important explanation of this issue stems from the work of Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter. He speaks of “creative destruction”2, which can be applied here as follows:

- Strong firms drive weak firms out of a market where resources are scarce.

- These stronger firms “create” better productivity and prosperity and “destroy” economic processes and firms that cannot compete.

- Often these firms are smaller, younger firms, perhaps even start-ups, for whom access to debt capital is an essential source of growth.

- If access is reduced in favour of less efficient firms, or even those near default, then the creative destruction process is impaired.

Monetary policy plays a key role here. Lower interest rates and a relaxed credit policy should be stimulatory for economic growth. However, this has to be conditioned on the quality of the borrower.

If the borrower is high quality and will use the debt to increase productivity and profit, then the expected stimulatory behaviour follows. However, if the borrower is lower quality, or the loan is made to prevent default, then the capital is misallocated and the result is lower efficiency and productivity.

We have also seen a secondary driver of this effect. The most productive and efficient firms, especially those in the tech sector, have little need for debt capital. Their profitability funds their expansion and reduces the need for debt. The supply of debt capital is therefore directed disproportionately towards lower return on equity (ROE), lower quality firms, or is not allocated at all.

The impact of the GFC

The term “zombie firm” was coined pre Global Financial Crisis (GFC), probably by Edward Kane from Boston University, when discussing the forbearance policy of the FSLIC (Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation) in dealing with economic insolvencies in savings and loans (S&Ls) in the late 1980s3.

Post the GFC, this artificial life was extended globally, with quantitative easing, artificially low interest rates and avoidance of corporate default and bankruptcy (bailouts, especially in the banking sector).

This process was intended to keep credit flowing, firms operating and the population in reasonable levels of employment, until economic growth returned and the life support could be switched off.

While a seemingly good policy to avoid an economic meltdown following the GFC, there have been unintended consequences. Strong economic growth came with reduced productivity.

It is difficult to see where this productivity problem might be solved. Much stock is placed in the potential for ongoing technological breakthroughs, like artificial intelligence or quantum computing. But without such a step change, and without proper allocation of capital to more productive ends, productivity could continue to be insipid.

The COVID effect

The global pandemic we are now experiencing has extended the cycle of low interest rates for the foreseeable future. Among other implications, this means further support for zombie firms, and a prolonged period of (necessary) support for firms and industries in financial difficulty.

There is no question that huge financial stimulus, relaxed credit default policy and low interest rates are necessary to soften the blow to the economy. However, the process of creative-destruction is somewhat suspended, and this has implications for the economy and financial markets in ways which will play out for many years to come.

Questions we need to ask from here:

- For how long will the current monetary policy and lax credit policy now be in place?

- Do we expect to see bankruptcies anyway? Can they be managed?

- Can the stimulatory policy we are currently seeing be directed towards stimulating the economy without allowing a wave of defaults?

Zombie firms can alter their zombie state by one of two means; increasing profitability and recovering, or exiting via bankruptcy. Neither appears to be happening. As Frank Borman, a US astronaut and businessman, once said: “Capitalism without bankruptcy is like Christianity without hell.”4

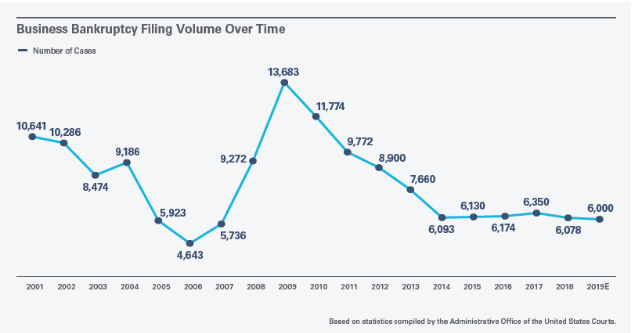

We have entered a world where bankruptcy is becoming increasingly rare – at or near an all-time low in history. The chart below5 is US bankruptcies by number since 2001 (that is, companies that have filed for bankruptcy protection under Chapter 11 of the US Bankruptcy Code):

Source: JDSUPRA, “Restructuring Market Trends”, Data as at December 2018.

Long Term Value Underperformance

A less obvious conclusion might be that this low interest rate/lax credit policy has been in force largely since the GFC, around 2008 and 2009, and has continued to the present day - and COVID may force this policy to continue.

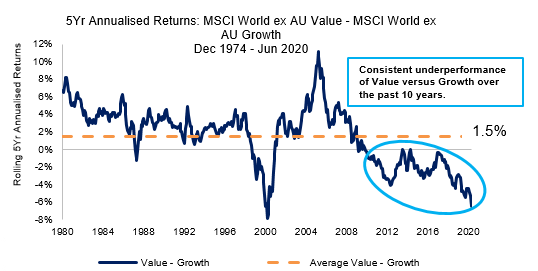

This coincides almost exactly6 with the period when value has continually underperformed growth7. The chart below shows a five year rolling average of value performance compared to growth in the MSCI ACWI ex Australia universe:

Source: Realindex, Factset. Data as at June 2020.

The two principal components of post GFC monetary and credit policy have been:

- Low interest rates

- Forbearance (i.e. lax credit policy)

We already know that low interest rates will inflate long term cash flows, making growth firms look more valuable when compared to value firms. Can we also conclude that some of the long term underperformance of value is due to forbearance as well?

Could the inefficient allocation of capital be preventing value firms from a mean reversion upwards, while at the same time locking zombie firms in so they cannot go bankrupt and be restructured?

We would contend that the existence and growth of the class of zombie firms has been a major contributor to this lack of migration, in particular the upwards migration of value stocks. The allocation of capital to these firms has meant that they (a) stay as zombies and so stick in the value category and (b) prevent capital being provided to firms that might actually migrate (the living).

Conclusions

As noted above, there are three conclusions we can draw here. The low interest rates and lax credit policy since the GFC (and now continuing after COVID) have artificially supported firms that might otherwise have gone bankrupt. Many of these firms will never recover, but are being prevented from this bankruptcy – zombie firms, the “undead”. It appears that this:

- Represents an inefficient allocation of capital

- Will depress future economic growth

- May help to explain the underperformance of value over the last 10 to 12 years

We have two future papers in the works. The first looks at zombie stocks using Realindex data sets, to attempt to replicate and better understand the phenomenon. A second paper will look into how a quality overlay can act as a “zombie-repellent”, and how the Realindex investment process captures this idea.

1 Value refers to a style of investing where investors prefer stocks that seem undervalued in the market and are generally cheaper.

2 Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1942). Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. Schumpeter used this idea to predict the demise of capitalism, following the work of Marx

3 Kane E. (1987): “Dangers of Capital Forbearance: The Case of the FSLIC and “Zombie” S&Ls”, Contemporary Economic Policy

4 The Growing Bankruptcy Brigade, TIME magazine (18 October 1982)

5 From https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/restructuring-market-trends-93876/

6 Coincidences may be just that, but imagine a world without them.

7 Growth refers to a style of investing where investors prefer stocks that offer strong earnings growth and are generally more expensive.

This material has been prepared and issued by First Sentier Investors (Australia) IM Ltd (ABN 89 114 194 311, AFSL 289017) (Author). The Author is a related body corporate of First Sentier Investors Realindex Pty Ltd (ABN 24 133 312 017, AFSL 335381) (Realindex). Both the Author and Realindex form part of First Sentier Investors, a global asset management business. First Sentier Investors is ultimately owned by Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, Inc (MUFG), a global financial group. A copy of the Financial Services Guide for the Author is available from First Sentier Investors on its website.

This material contains general information only. It is not intended to provide you with financial product advice and does not take into account your objectives, financial situation or needs. Before making an investment decision you should consider, with a financial advisor, whether this information is appropriate in light of your investment needs, objectives and financial situation. Any opinions expressed in this material are the opinions of the Author only and are subject to change without notice. Such opinions are not a recommendation to hold, purchase or sell a particular financial product and may not include all of the information needed to make an investment decision in relation to such a financial product.

To the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted by MUFG, the Author, Realindex nor their affiliates for any loss or damage as a result of any reliance on this material. This material contains, or is based upon, information that the Author believes to be accurate and reliable, however neither the Author, MUFG, Realindex nor their respective affiliates offer any warranty that it contains no factual errors. No part of this material may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of the Author.

In Australia, ‘Colonial’, ‘CFS’ and ‘Colonial First State’ are trade marks of Colonial Holding Company Limited and ‘Colonial First State Investments’ is a trade mark of the Commonwealth Bank of Australia and all of these trade marks are used by First Sentier Investors under licence.

Total returns shown for the Fund(s) have been calculated using exit prices after taking into account all ongoing fees and assuming reinvestment of distributions. No allowance has been made for taxation. Past performance is no indication of future performance.

Copyright © First Sentier Investors (Australia) Services Pty Limited

All rights reserved.

Get the right experience for you

Your location :  Australia

Australia

Australia & NZ

-

Australia

Australia -

New Zealand

New Zealand

Asia

-

Hong Kong (English)

Hong Kong (English) -

Hong Kong (Chinese)

Hong Kong (Chinese) -

Singapore

Singapore -

Japan

Japan

United Kingdom

United Kingdom