Corporate bonds have performed well over the past year or so, since the Covid shock in early 2020.

Like shares, credit valuations dipped quite sharply in February and March last year as investors digested the implications of the coronavirus pandemic; specifically the probability of a deterioration in company profitability and a slowdown in global growth. The strength of the subsequent rebound has prompted several clients to enquire whether we think credit still offers value.

This article answers that question, from two different angles.

First, we outline why we believe there’s a case for making a structural allocation to credit within a diversified investment portfolio. Second, we look at current valuations, and consider whether there’s a cyclical case for owning credit at this point, given current valuations.

For the purposes of this paper, we are focusing on the investment grade corporate sub-sector, because our Global Credit strategies are predominantly focused on this part of the market.

The structural case for credit

Many investors already have some indirect exposure to credit, through allocations to aggregate or composite-style fixed income funds. Most of these strategies are predominantly invested in government bonds, but can have smaller investments in credit markets too. Fewer investors have a direct, standalone allocation to credit. This is interesting considering credit securities can offer higher prospective returns than other defensive exposures, like government bonds and term deposits.

A permanent allocation to credit can make sense from a strategic asset allocation perspective. Independent research1 suggests there is merit in carving out a permanent, standalone credit allocation within a diversified investment portfolio. For some, this might involve a partial reallocation of capital from composite/diversified fixed income exposures in favour of credit. For others, it may involve reducing the size of existing investments in term deposits, or other cash-based strategies.

It is not possible to replicate the risk/return characteristics of global credit markets by holding a combination of higher risk equities and lower risk government bonds. Over the long term, corporate bonds have achieved superior risk-adjusted performance than a combination of Treasuries and equity of the same companies. The outperformance is evident irrespective of what time period is measured, and also by rating, sector and geography2. With risk-free rates so low, there has arguably never been a better time to consider a structural allocation to higher yielding credit markets. To underline the relative merits of the asset class, it is worth observing historical spreads and default rates and, in turn, the return profile of credit versus comparable government securities.

Spreads and default rates

All credit securities have some level of embedded default risk. To entice investors and to compensate them for this default risk, credit securities offer yields over and above the risk-free rate. This premium is known as the credit spread. The size of the spread fluctuates over time, influenced by the evolving level of perceived default risk.

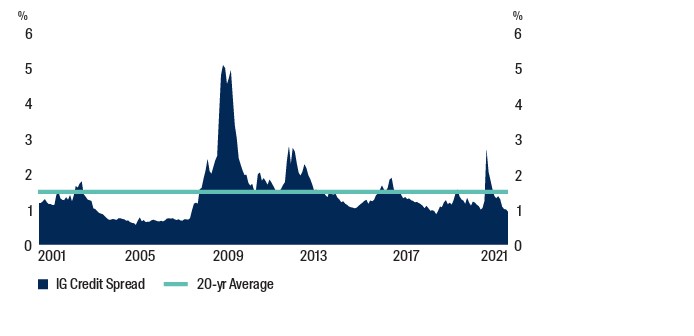

As shown in Figure 1, investment grade spreads have rarely dipped below 1% and have averaged 1.43% over the past 20 years. Extending the time horizon back more than 30 years, in developed markets like the US, average spreads are nearer to 1.20%. The slightly higher premium in the more recent period primarily reflects changing liquidity in credit markets and, arguably, a better estimate of risk in the post-Global Financial Crisis (GFC) period.

Figure 1 – credit spread history

Source: Bloomberg. Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Corporate Average Option Adjusted Spread. 1 January 2001 to 28 February 2021

The key question, therefore, is whether that 1.43% is sufficient to compensate investors for the level of embedded default risk. To answer it, we must look at default and recovery rates, and the potential for capital impairment.

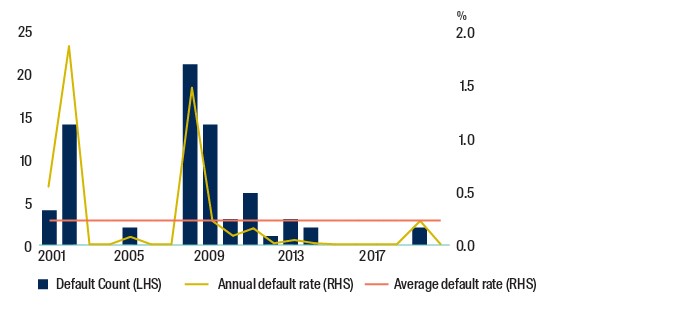

Figure 2 – Annual default counts and rates

Source: Moody’s Investors Service 2020 Defaults and Recovery Report

The term default is a rather scary prospect for investors; nobody likes the idea of losing money. According to Moody’s, however, the frequency and magnitude of defaults is less concerning than investors might think, at least in the investment grade sub-sector (default rates are higher in the more speculative, sub-investment grade sector).

As shown in Figure 2 above, there were no defaults at all among investment grade corporate issuers in nine of the past 20 years. And in the period as a whole, the average default rate was just 0.23% pa on a volume-weighted basis. Perhaps not quite so scary, after all.

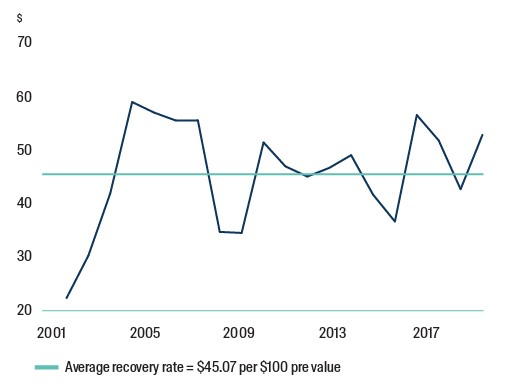

Moreover, investors can typically claw back some capital following an issuer default. As shown in Figure 3, investors have, on average, been able to recover 45 cents in the dollar from defaulting issuers over the past 20 years.

Figure 3 – Recovery rates

Source: Moody’s Investors Service 2020 Defaults and Recovery Report; global defaulted bond and loan recovery rates (per $100 par)

The actual cost of defaults is therefore around half of what headline default rates might indicate. The recoveries not only help preserve capital, but also support positive excess returns from credit over the full market cycle.

Perhaps even more importantly, the frequency of defaults and the extent of capital impairment in Global Credit portfolios can be significantly lower than these market-wide indications suggest. Over the past 20 years, for example, our flagship Global Credit strategy has experienced just four defaults in the investment grade sub-sector, compared to 72 in the broader market universe. The impact of these defaults on performance has consequently been lower than for the broader market. This highlights the value of diligent credit research, and underlines the merit of active management in this asset class.

Excess returns

It is also insightful to compare historic credit returns against comparable government bonds, to see the ‘excess return’ over and above risk-free rates. Exchange rate movements can conceivably contribute to return volatility from both credit and government bonds, although we have stripped out currencymovements from the analysis as most credit investors fully hedge FX risk.

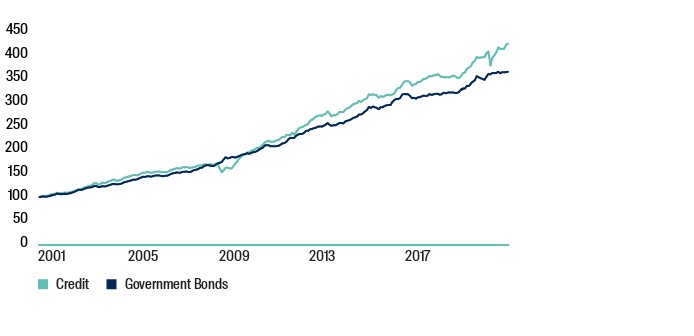

Figure 4 – Cumulative returns from government bonds and global credit

Source: Barclays Live. Government bonds = Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Treasuries Index; Credit = Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Corporate Index. Returns shown 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2020, indexed to 100 at 1 January 2001.

As shown in Figure 4 on the previous page, the excess return from credit – which includes the adverse influence of defaults – becomes more pronounced over time, with the benefit of compounding. Risk-averse investors with only government bonds in their fixed income allocations, or those favouring cash and term deposits with no exposure to bonds at all, are missing out on this potential outperformance.

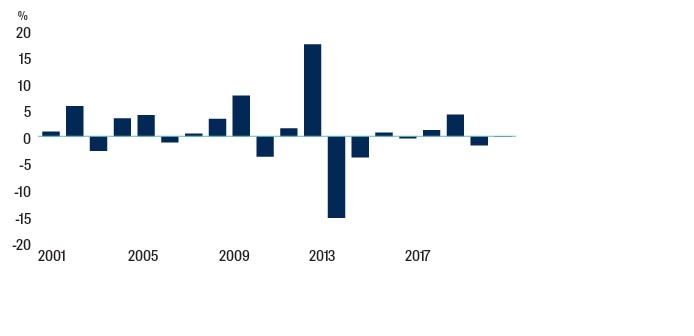

Whilst positive over time, the excess returns from credit are not uniform, and fluctuate over the cycle. Over the past 20 years, and as shown in Figure 5 below, excess returns have been negative 40% of the time; in eight of the past 20 years. This statistic may be disconcerting for investors, but it is important to note that credit markets have always rebounded from temporary drawdowns. Ultimately, as long as issuers do not default, a combination of coupon income and the repayment of bond principal at maturity will generate positive returns, potentially over and above those from comparable government securities.

Figure 5 – Calendar year excess returns from global credit, AUD-hedged

Source: Barclays Live. Excess returns are shown for corporate bonds (Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Corporate Index) over government bonds (Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Treasuries Index). 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2020

Most notably, excess returns exceeded 17% in 2009 following underperformance during the GFC. Similar themes have been seen since; excess returns were strong in 2012 and 2019, for example, following weakness in the preceding years. Even in 2020, excess returns were positive in the year as a whole as credit bounced back very strongly from the sell-off in February and March. These typically swift upturns in valuations reward investors who persevere with the asset class during periods of uncertainty, and can help credit markets generate potential positive excess returns over full market cycles.

The numbers are clear and compelling. Over the long term, credit spreads have more than compensated investors for actual default risk. And the benefit of the credit spread means credit markets have been able to meaningfully outperform government bonds over time. We believe a structural allocation to credit can therefore meaningfully improve the risk/return profile of a diversified investment portfolio over the long term.

The cyclical case for credit

As we saw in Figures 4 and 5, the performance of corporatebonds is cyclical in nature. Fluctuations in credit spreads will always be a feature of the market, but should not be concerning for investors as long as default risk remains manageable. Whilst spreads fluctuate over the life of a credit security, they typically compress as bonds approach maturity and as the perceived risk of owning the security falls.

Conventional bond market theory suggests credit will outperform during periods of economic expansion, and fare less well as the economic cycle matures. Historically, credit has performed well in a ‘goldilocks’ economic growth scenario – not-too-hot, but not-too-cold – whereas equities tend to perform better as growth increases. With credit, ideally investors don’t want too much inflation eroding their capital, but they don’t want deflation either.

Deciding whether now is a good time to make a new allocation to credit might therefore depend on investors’ views of where we are in the cycle. Are we closer to the end, following a multi-year bull market in risk assets, or closer to the beginning, with large-scale fiscal stimulus packages ready to fuel the next phase of global growth?

Investors’ ongoing search for yield is a relative game

We understand that the current prospective income of around 2.3% pa3 from investment grade credit is insufficient to get the pulse racing for many investors. In fact, ‘all in’ yields (the risk-free rate, plus the credit spread) have rarely been lower. That said, prevailing credit yields must be considered alongside prospective income from other defensive assets.

Ten-year Australian Commonwealth Government bonds are yielding less than 1.5% pa currently, while yields on equivalent securities in Europe and Japan are even lower4. Term deposit rates in Australia and elsewhere have plummeted too. Unfortunately, it is very hard to find compelling yields anywhere currently. Savers and investors who rely on income have been among the indirect casualties of Covid-19.

In our view, there is merit in holding an allocation to credit within a well-diversified portfolio, particularly with government bond yields as compressed as they currently are. And, perhaps even more importantly, we believe there is room for credit valuations to improve a little further, despite the strong rally we have already seen in the asset class. Moreover, with credit valuations more attractive in some areas of the market than others, there is scope for active managers to allocate strategically to regions and sectors where valuations are most attractive from a risk/return perspective.

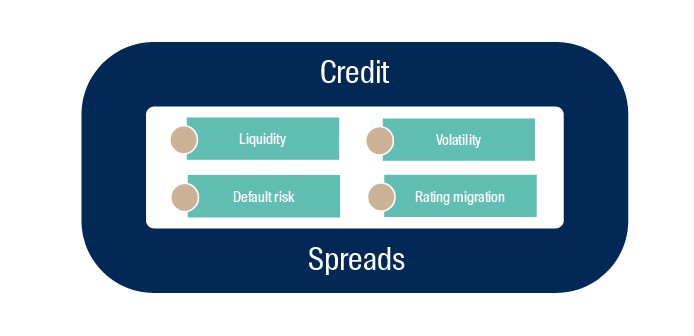

Deconstructing credit spreads

Credit spreads compensate investors for various risk factors, but liquidity, volatility, default risk, and ratings migration risk are arguably the most important. With that in mind, it is worth considering each of these four drivers individually, to see how they might affect valuations in the remainder of 2021 and beyond.

Liquidity

Part of a corporate bond’s yield premium over comparable government securities compensates investors for liquidity risk – the prospect of buyers disappearing when investors want to sell their holdings. This phenomenon reared its head during the GFC in 2008 when, for a period, it was challenging to trade credit securities at any price. Liquidity dried up again in March 2020 during the Covid shock, although it recovered quite quickly.

The recovery in demand partly reflected the actions of central banks. Determined to avoid a catastrophic market event like the GFC, major central banks – including the US Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, Bank of England, and Bank of Japan – announced asset purchase programs to help stabilise markets. Central banks bought large quantities of bonds on the open market, in order to maintain market stability in case of a prolonged period of Covid-related uncertainty. These facilities provided important support to credit markets for the remainder of 2020, and continue to underpin valuations today.

Demand in secondary markets has also been strong, even during the Covid panic in early 2020. Daily transaction values5 suggest there is plenty of money sitting on the sidelines, ready to be deployed in yielding investments as and when opportunities are identified. For now at least, investors appear comfortable investing in the asset class, in the knowledge that central banks will likely increase the pace of their bond purchases to support valuations on any sign of weakness.

These facilities remain in place in many major markets, although the US Federal Reserve’s bond buying program was withdrawn at the end of December. Only a fraction of the money set aside in this scheme was ever actually utilised – the support mechanism was ultimately not required, as US credit markets regained their poise after the sell-off in February and March. The removal of the program should not be viewed as a negative, in our view. The Federal Reserve would likely step up again if spreads started to widen substantially, potentially providing a backstop for valuations. This appears to be reassuring for investors: as we saw in March 2020, policymakers can and will respond rapidly and decisively when financial market stability is threatened.

Volatility

Like the liquidity premium, credit spreads partly compensate investors for the probability of volatility.

This will remain the case going forward, although we believe support from central banks will ensure volatility does not spike as aggressively as it did a year ago. As outlined above, policymakers are determined to keep markets operating normally during this unusual period, and have the firepower to increase the scale of asset purchases, if required.

With the implicit support of the Federal Reserve removed for now, attention has switched to other sources of demand to help gauge whether the recent credit rally can be sustained. Corporate bond markets globally enjoyed nearly A$300 billion of inflows in 20206. That is a lot of demand; a record level, in fact.

Companies tapped into this strong demand by issuing record volumes of new bonds, using the historically low borrowing costs as an opportunity to bolster their balance sheets. Outstanding debt among investment grade issuers in the US rose by around 9% during 20207. Maintaining excess liquidity on the balance sheet essentially provided some extra insurance, designed to help companies withstand any prolonged period of sub-par growth owing to a second wave of Covid, or other unrelated drivers of economic weakness.

Encouragingly, almost all of the new supply was met with strong demand. New issues in the second half of 2020 were typically several times over-subscribed, underlining investors’ appetite for income-producing investments.

With government bond yields and term deposit rates so low, and with central banks confirming that policy settings are unlikely to be amended any time soon, there appears limited scope for yields on other defensive investments to rise meaningfully in the near term. In turn, income-starved investors might continue to look up the risk spectrum in search of income, supporting demand for credit. This theme is providing a strong tailwind for credit and suggests the volatility premium might remain low for the foreseeable future.

Separately, the improving economic outlook is supportive of credit fundamentals. Any perceived reduction in default risk should, all else being equal, drive volatility lower as the probability of undesirable outcomes is reduced.

Default risk

A higher risk of default is arguably the most obvious reason whycorporate bonds offer yields above comparable government securities. It also helps explain why credit spreads increased so much early last year; the likelihood of a precipitous drop in global growth prompted investors to suggest corporate failures would rise sharply. The concern was understandable, although defaults did not increase anywhere near as much as had been forecast at the height of the Covid sell-off.

The better-than-expected default outcome was helped by enormous fiscal support programs that were rolled out by governments around the world. Income support payments to individuals, direct financial support packages to small- and medium-sized enterprises, and changes to corporation tax regimes all provided important pillars of support to companies and corporate earnings have been quite resilient.

Almost all US-listed companies have now released their financial results for the December quarter, and for the 2020 year as a whole. Whilst down on a rolling annual basis due to the impacts of Covid-19, the results were strong relative to expectations from a few months ago. Collectively, companies have benefited from fiscal stimulus programs in key regions and, in many cases, have adapted to virus-related challenges by reining in capital expenditure and lowering costs. These moves might seem like common sense, but they have had a meaningful influence on the bottom line.

Even more importantly, earnings are expected to improve significantly this year. Consensus forecasts suggest earnings among S&P 500 companies in the US will rise more than 40%8 this year from 2020 levels. This is important for credit investors as well as shareholders, because rapid earnings growth typically results in lower leverage for borrowers. Current net debt levels should not be a concern for credit investors if earnings growth accelerates, as anticipated.

As well as the potential for higher earnings, there are some other powerful forces that could remain supportive of credit.

Fiscal support programs are ongoing. These schemes are supporting economic activity and company profitability and there is scope for them to be upscaled. In the US, for example, President Biden has recently announced a new US$1.9 trillion spending program, on top of the US$2 trillion and US$900 billion programs rolled out during 2020. This additional support should act as a tailwind for company profitability.

The rollout of vaccines in major markets. Assuming efficacy rates remain high, vaccines should enable social distancing restrictions to be lifted gradually. In turn, this should pave the way for a strong and sustainable rebound in economic activity levels. As restrictions are eased and as employment increases towards long-term average levels, we expect to see an increase in discretionary spending, with pent-up demand driving higher consumption.

Lower borrowing costs for companies. Despite higher volumes of corporate bonds on issue, interest expenses did not increase much, if at all, during 2020. With credit spreads and government bond yields significantly below pre-Covid levels, borrowing costs have declined sharply for most companies. Lower borrowing costs can be particularly beneficial when existing corporate bonds mature and as new ones are issued. The lower repayments ease the debt burden for companies, much like lower mortgage repayments benefit homeowners.

Furthermore, firms are locking in the current, historically attractive yields for extended periods. The duration of credit indices has lengthened as a result, and should be positive for credit risk overall as companies have secured long-term financing at attractive rates.

The anticipated improvement in earnings should also lift interest coverage among issuers, meaning they can service their debt repayment obligations more comfortably.

While these indicators are encouraging and suggest default rates should remain low, under-estimating default risk would be imprudent. Corporate failures can result in permanent capital impairment, and can erode returns from corporate bond portfolios. Ultimately, default risk is ever-present in credit, irrespective of the economic cycle and the anticipated performance of individual firms. We therefore remain watchful, but at this stage we believe default risk is moderating and do not expect it to materially affect credit spreads in the foreseeable future.

Ratings migration

The operational and financial performance of a firm, and its ability to service its debt repayment obligations, can result in upgrades or downgrades to credit ratings over time. This is known as ratings migration. A corporate bond currently rated ‘A-’, for example, mightbe upgraded to ‘A’ if the firm is performing well, or could be downgraded to ‘BBB+’ or lower if the outlook for profitability deteriorates. These ratings are important, as they influence the cost of debt when new bonds are issued; in general, the lower the credit rating, the higher the yield required to attract investors.

Ratings downgrades can also adversely affect the price of existing securities, as investors reprice default risk. That is why we monitor credit investments extremely closely. All holdings undergo constant analysis by a large team of dedicated, in-house credit analysts. The intention is to remove deteriorating issuers from portfolios before default risk starts to materially affect valuations.

We are particularly mindful of ‘fallen angels’: credits rated ‘BB+’ or above (investment grade) that are de-rated into the high yield category (‘BB’ or below). These downgrades can have a particularly negative impact on prices, as they can result in forced liquidations by some market participants. ‘Investment grade only’ funds might be unable to maintain their exposure, for example, and could be required to sell the bonds. For those interested in understanding this specific issue in more detail, we published a paper on the topic in 2018, available here.

Again, while the risk of ratings downgrades is ever-present in credit, we believe it is manageable and should not unduly affect valuations in the asset class as a whole. Indeed, the likelihood of an uplift in earnings means we may even be at the beginning of a broad ratings upgrade cycle.

Risks to the investment thesis

Before wrapping up, and in the interests of a balanced view, it’s worth looking at some of the factors that could prompt a change in our cautiously optimistic view.

A delayed economic rebound

Perhaps most importantly, credit markets would look expensive if economic growth does not rebound as strongly as anticipated. Like others, we were encouraged in January when the International Monetary Fund increased its global GDP growth forecast for this year by 0.3%, to 5.5%9. If these forecasts prove too optimistic, however, it would become more difficult to justify current valuations.

For now, investors seem comfortable looking beyond the current subdued economic performance, buoyed by vaccine-related optimism and governments’ commitment to providing seemingly limitless levels of fiscal support. But that could change, perhaps if existing vaccines prove less effective than anticipated against new Covid variants. There is always a chance that further extended lockdowns are required in key regions, clouding the outlook and prolonging the anticipated rebound in GDP growth.

The potential impact on risk assets, including credit, could be cushioned to some degree by higher levels of government support, if required. Nonetheless, a W-shaped economic recovery, with a further leg down before any meaningful improvement, would likely weigh on corporate profitability, sentiment towards credit markets, and spreads – at least in the short term. Equity markets would likely be similarly affected, potentially selling off if the anticipated global recovery is delayed.

Higher leverage

Leverage is an important metric for credit issuers. Increases can result in credit rating downgrades and, during periods of market stress, can develop into something more sinister. As we saw in 2008, heavily-indebted companies can find it increasingly difficult to service their debt during prolonged downturns, eventually resulting in rising default rates.

Companies – certainly in the financials sector – appear to have learned some lessons from the GFC and, in many cases, have lowered their leverage over the past decade or so. Moreover, leverage is expected to decline this year as earnings growth outpaces increases in net debt. Nonetheless, there is always a risk that companies take on higher debt levels and stretch their balance sheets, convinced perhaps that fiscal support will continue to underpin their earnings indefinitely. Any meaningful increase in borrowing levels and leverage would be a red flag; at a minimum it could prevent spreads from narrowing any further, limiting potential returns from the asset class.

It is also worth noting that dividend payout ratios fell to a six-year low in 202010, as companies sensibly decided to retain cash on the balance sheet. We can expect shareholders to call for higher dividends going forward, however, which is something to keep an eye on in the months ahead. We would be perturbed if most of the excess cash was used to increase dividends rather than to pay down existing debt, as this could result in higher leverage and deteriorating interest coverage.

More than two decades of expertise

First Sentier Investors has been constructing credit funds for more than 20 years, so we have the expertise and know-how to manage investment risks over the full credit cycle.

Whilst we are always looking for value-adding opportunities within the asset class, we believe First Sentier Investors is among the most conservative credit investors in the Australian peer group. We understand that a credit allocation sits within the defensive component of most investors’ portfolios, and is intended to provide some offset to potential volatility in growth assets. Accordingly, capital preservation is of paramount importance in our Global Credit strategy. We invest a lot of time and energy researching issuers and monitoring their performance, to help detect any early signs of stress. The intention is to remove deteriorating issuers from portfolios before valuations are meaningfully affected. Responsible investment considerations form an important component of the research and investment processes. Environmental, Social and Governance risks and how they are being managed by issuers help influence the assignment of internal credit ratings, which in turn drive portfolio construction decisions.

More information on our credit research process is available here.

1. Source: Barclays Quantitative Portfolio Strategies research: ‘Is Credit a Redundant Asset Class?’,January 2020

2. Source: Barclays Quantitative Portfolio Strategies research: ‘Is Credit a Redundant Asset Class?’,January 2020

3. As at 28 February 2021. Source: Bloomberg.

4. As at 28 February 2021. Source: Bloomberg.

5. Source: Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine (TRACE)

6. Source: Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine (TRACE)

7. Source: JP Morgan research, 9 December 2020

8. Consensus earnings forecasts for S&P 500 Index constituents, as at 9 March 2021. Source:

9. Source: IMF World Economic Outlook Update: January 2021

10. Source: JP Morgan research, 9 December 2020

Important Information

This material has been prepared and issued by First Sentier Investors (Australia) IM Ltd (ABN 89 114 194 311, AFSL 289017) (Author). The Author forms part of First Sentier Investors, a global asset management business. First Sentier Investors is ultimately owned by Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, Inc (MUFG), a global financial group. A copy of the Financial Services Guide for the Author is available from First Sentier Investors on its website.

This material contains general information only. It is not intended to provide you with financial product advice and does not take into account your objectives, financial situation or needs. Before making an investment decision you should consider, with a financial advisor, whether this information is appropriate in light of your investment needs, objectives and financial situation. Any opinions expressed in this material are the opinions of the Author only and are subject to change without notice. Such opinions are not a recommendation to hold, purchase or sell a particular financial product and may not include all of the information needed to make an investment decision in relation to such a financial product.

To the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted by MUFG, the Author nor their affiliates for any loss or damage as a result of any reliance on this material. This material contains, or is based upon, information that the Author believes to be accurate and reliable, however neither the Author, MUFG, nor their respective affiliates offer any warranty that it contains no factual errors. No part of this material may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of the Author.

Get the right experience for you

Your location :  Australia

Australia

Australia & NZ

-

Australia

Australia -

New Zealand

New Zealand

Asia

-

Hong Kong (English)

Hong Kong (English) -

Hong Kong (Chinese)

Hong Kong (Chinese) -

Singapore

Singapore -

Japan

Japan

United Kingdom

United Kingdom